Colours of Passion and the Politics of Art

Colours of Passion

and the Politics of Art

Art has been a subject of debate and discussions throughout history.

Several artists had to face opposition from others for the elements portrayed

in their artworks. ‘Freedom of Expression’ is a term that has been often contested.

But how much liberty does an artist have to express in the name of art? Is art

independent of menial politics, or is it obliged to abide to politics for its

survival? These questions remain valid in all societies and at all times.

Although acclaimed critically for its depiction of art

elements, Ketan Mehta’s Rang Rasiya (Colours

of Passion) is not his best artwork, especially when we expect it from the same

director, who has given us Mirch Masala

and Mangal Pandey: The Rising. Perhaps

it is due to the jam-packing of numerous topics such as the biopic, the unusual

love story of an artist and the societal issues prevailing in the colonial 19th

century put into a tight frame that overloads the screentime of the film. But there are several reasons that make

watching Rang Rasiya worthwhile: particularly

the themes in the film and the issues that it raises regarding the censorship

of art.

Released in 2014, Rang

Rasiya is a film starring Randeep Hooda and Nandana Sen. Based on the Marathi

novel by Ranjit Desai, this film is a biopic of the celebrated 19th

century Indian painter Raja Ravi Varma – who is now remembered as the artist

who visualized the faces to Indian Gods and Goddesses in the contemporary

times.

The storyline describes the chronicles of Raja Ravi Varma,

his colourful artistic journey, his relationship with others and his

perspectives regarding art and freedom of expression. Although many Indians are

familiar with his artworks (or atleast familiar with him as a legendary artist),

his life story has remained largely unknown outside the realm of art. There are

a very limited works based on the life of Raja Ravi Varma. Hence, the first

reason why Rang Rasiya is a unique

movie is because it deciphers the life of this great painter on the

silverscreen, whose perspectives on art remain valid – even to this modern day.

The plot largely revolves around two topics: his

relationship with Sugandha – his artistic muse and his argument regarding

freedom of expression which is challenged in the court. Raja Ravi Varma is

portrayed as a liberal painter in the film who does not hesitate to express his

opinions – both in his works, as well as in public.

Raja Ravi Varma and His Artworks

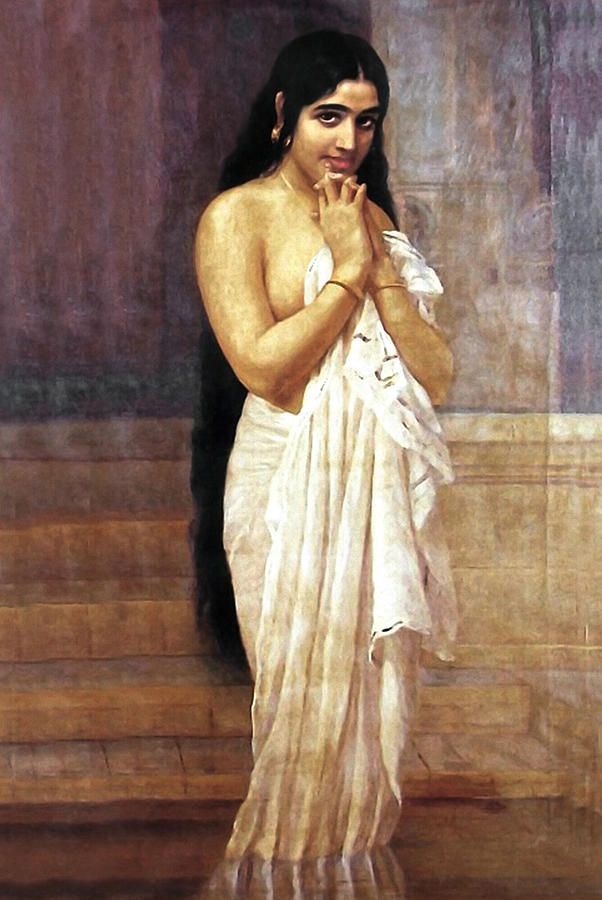

(South Indian Girl After Bath: A painting by Raja Ravi Varma)

Born in Kilimanoor in Kerala, Raja Ravi Varma moves to

Bombay after the death of the King of Travancore, who was his former patron. In

Bombay, he becomes acquainted to Sugandha, a courtesan, who becomes his muse

and the model for his artworks. Raja Ravi Varma is so enchanted with her beauty

that he paints Goddesses and Mythological figures by giving them her face. In

the meantime, under the patronage of the king of Baroda, he paints an entire

collection for the royal gallery which is exhibited to the public. This makes

him highly popular in the society, but segregates his audience into two

segments: His admirers and his critics.

The Notion of Art versus Religion

(Painting of Goddess Saraswathi by Raja Ravi Varma)

Varma’s admirers are largely the liberals and the commoners.

The commoners, who were not able to visualize their Gods, now feel redeemed

upon seeing his paintings. The biggest motivation in this regard comes when he watches

devotees fall in front of his painting of Lord Sri Ram, praising and chanting

Ram’s name. This in turn inspires him to open a printing press that produces

the lithographs of Indian Gods at an affordable price for the public. It is

noteworthy to remember that this measure has made his artworks so popular that

billions of households in India worship these portraits with great veneration

even today.

The historic relevance of Varma’s contribution to Indian

society is hinted in the film i.e.when the lower class Kamini tells Raja Ravi

Varma that her caste had become a barrier for her community to enter the

temple. But she thanks him for bringing the God out of the temple and making Him

accessible to all. In this regard, Raja Ravi Varma can be viewed as a social

reformer whose art brought people closer to the divinity.

Sadly, Varma's critics in the film turn out to be self-sanctioned

religious moralists who question and condemn him for giving visual identities

for their Gods. They even take the matter to the court by filing a lawsuit

against him for hurting their religious sentiments. They are particularly

offended by his painting of King Pururavas and Urvashi, which they term as a

work of pornography. Raja Ravi Varma’s morality as an artist is questioned in

the court.

The Notion of Art versus

Consumerism

Raja Ravi Varma holds a view that art must be accessible to

all. Especially when his paintings comprise religious significance and is

adored by the masses, he feels an urge to open a printing press to produce

copies of his art in thousands. Interestingly, this is one instance in the

history where an artist himself sanctions the production of kitsch of his

artwork. However, these lithographs may not be regarded as ‘kitsch’ in the

regular sense, as they appealed to the emotions of the masses religiously and

are held at an honourable place in every home.

In the film, Raja Ravi Varma approaches Govardhan Das, a wealthy

businessman, seeking assistance to sponsor his press. Govardhan Das agrees to

run the press on partnership, since he believes that ‘an artist is not capable

of handling business all by himself.’ Here one may observe the perspectives of

Raja Ravi Varma – an artist by profession desires to commercialize his

artwork, but with a deeper intention. Though the press performs well – the

business devastates upon the breaking of the historic plague epidemic in the

late 1890s. Over the course of events, the press is set on fire – either by the

self-sanctioned religious moralists, or by Sugandha’s emptor, who learns about

her relationship with Varma.

The Notion of Freedom

of Expression

(Urvashi and Pururavas by Raja Ravi Varma)

When Govardhan Das refuses to restore the press, Varma

deposits him his paintings as a gage and re-launches the press. As a result,

his glamorous painting of Urvashi is printed without his knowledge – resulting

in Sugandha facing criticism from society and mockery of her character, as well

as the self-sanctioned religious moralists filing a lawsuit against him by

accusing him for promoting pornography in the name of art.

Sugandha is summoned by the court too, and questioned

whether she willing posed for his painting. When her character is questioned by

the lawyer, she replies by affirming, she believes that Raja Ravi Varma is a

true artist. Then she says the following lines – “Aap nahin rehenge, main nahin rahoongi. Par iski kala rahegi – Hamesha.

Aur iski zariye – Main bhi” (You would not last forever, so do I. But his

art will – Forever. And with it – me too). These are the most sincere lines in

the entire film that explains the relationship between an artist and the

inspiration behind his artwork.

And, the Notion of Censorship of Art

This brings us to the final question of this essay – How

free are we to express ourselves through art?

Ironically, even Ketan Mehta had to fight against the Censor

Board of India for the release of Rang

Rasiya for almost six years for the same reason: The censorship of art.

As a film reviewer, you may feel that even after one hundred

years – the censorship of art has not reformed in India. In the film, it was

the self-sanctioned religious moralists who oppose Raja Ravi Varma by failing

to understand the fringe line between art and pornography. In our times, it is

the Censor Board that failed to certify this film for six years, citing the

offensive presence of a wide angle shot of Nandana Sen’s bare chest – that was

essentially required in the film, which inspires Varma to paint the portrait of

Urvashi.

In a country where cheap adult comedies that openly promote

vulgarity are certified by the Censor Board, a masterpiece of art – on art –

that celebrates art – is ironically censored on the basis of containing

pornographic elements. In a country, where billions of people light lamps in

front of the artworks of Raja Ravi Varma even today, his own story was censored

from being narrated to the audience on screen. Sadly, this is

the politics prevailing in the realm of art and its relationship with society.

End Notes:

Image Source: Internet

Film link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dUe37yJBad8

Comments

Post a Comment